Online teaching: what worked for me

Mar 28th, 2021

I’ve taught Harvard’s CS50 as a teaching assistant twice now, during the fall semesters of 2019 and 2020. Fall 2019 was, of course, taught in-person, whereas fall 2020 was a remote Zoom class, so my teaching experience changed dramatically due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, I found myself spending more time preparing lessons in my attempts to keep class engaging—not only because sections expanded from 75 to 120 minutes, but also because of the exhaustion of constant video conferences. In this post I want to share a few approaches that worked well for me, and may be helpful to others who teach introductory computer science online. I also want to note that nothing here is original. I read a fair amount of pedagogy research and blogs, which I’ve cited or linked to when I know the source; this post simply summarizes the specific techniques that worked for me in fall 2020.

Student feedback

By far, the most helpful thing I did in fall 2020 was to ask students questions about their learning experience in an anonymous survey at the end of each lesson. Because I was constantly receiving data about how students perceived my teaching, I was able to improve from week to week.

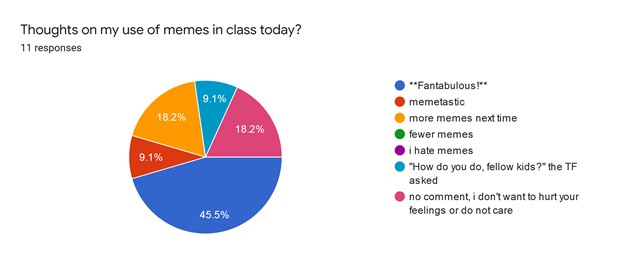

My use of memes in Week 7 was, according to a plurality of students, **Fantabulous!**

Knowing what students think while there’s still time to improve is much better than waiting for comments on end-of-semester evaluations.

My use of memes in Week 7 was, according to a plurality of students, **Fantabulous!**

Knowing what students think while there’s still time to improve is much better than waiting for comments on end-of-semester evaluations.

For example, my students noted at the beginning of the term that my time management of instructional time was not great—we were going for two hours straight, without a break, and were spending too much time on practice problems for students to be able to finish the lab they had to submit each week. This wasn’t because I didn’t plan time for breaks or the lab, but rather because I wasn’t holding myself accountable to the time limits I had set in my lesson plans. After students made these comments on the feedback form, confirming my own self-reflection, I worked to cut off activities in time to move on. They noticed the change and thanked me for listening to their feedback in later surveys.

Low barriers to participation

Many educators This is anecdotal. As this is a blog post and not an academic paper, I hope readers will forgive me for using the word “many” and for not digging up old Tweets as citations. have praised the wonders of the Zoom chat, and they’re absolutely right. The chat greatly lowers the barriers to participation—especially for shy students, it can be much easier to drop a message in the chat with a question than to use a digital “Raise Hand” button to get permission to unmute and speak before the entire class. For students who for whatever reason can’t unmute or turn their cameras on (a fire alarm rang in a student’s building for much of one class meeting), it can be a way to participate despite unexpected circumstances. And, perhaps most importantly, the chat feature provides a crucial community-building opportunity by allowing students to create moments of joy during class. Coursework should not be merely a long, rigorous slog through material. The chat feature allows students to make occasional jokes or cultural references when they’re not using it to discuss connections they’re making between the material and their past experiences and prior knowledge.

The chat is not the end of efforts to lower the barriers of class participation, though. During each section, my students were expected to have a tab open for quick polls. At first I used Poll Everywhere because Harvard pays for a license, but later in the semester I switched to PearDeck (which I now greatly prefer). I started each class meeting with a check-in, during which my students logged into the poll and answered the first question: “How are you doing?” It appears I took this idea from this article. After a few answers appeared on screen, I offered the space for any volunteers to describe their responses in more detail before we got started on the material for the day. Some students noted in their end-of-course evaluations that the weekly check-ins helped them get through the semester. For my part, I got to learn more about my students’ interests and difficulties each week.

After a discussion of each topic, I gave my students a few poll questions to test their understanding, allowing them to explain their own and respond to each other’s answers. (How many times will this for loop run? What does 5 % 3 yield?) These activities were designed to give me real-time feedback on students’ understanding and to give them agency over their learning, since they were expected to generate answers and explain their reasoning to peers.

Finally, I used breakout rooms to create smaller-scale learning spaces. I’m aware that many of my classmates hate breakout rooms, Again, anecdotal, but there are some pretty popular posts on the Harvard Confessions page to support this statement. but I disagree. As a student, I think they create a better environment in which to explore ideas with peers, and I’ve enjoyed the opportunity to propose solutions—and maybe fail—with the lowered stakes of a smaller audience. Some other students seem to agree, per Harvard Confessions. As a teacher, I think they help ensure active participation from (nearly) everyone, since a silent breakout room feels worse than at least trying to complete the task at hand. Active participation can also be ensured by using accountability tactics, like requiring each breakout room to contribute to a short Google Doc as they converse. Most importantly, though, is to give students a specific task and a time limit—15 minutes to try to write a recursive function to calculate a factorial is a lot easier for students to grasp than “discuss the differences between the sorting algorithms we learned about in lecture.” This is not to say that conceptual or theoretical discussions are out-of-bounds for breakout rooms. A better approach for these breakout activities is to give students a specific question to try to answer—“Apply so-and-so’s theory to case X.” Or, if you really do want to just jog students’ memories about the readings, consider mapping out some more specific guiding questions you hope will spark a conversation. A little structure goes a long way in helping students to engage with difficult topics.

Classroom culture

Fall 2020 was stressful, not only because Harvard is typically a stressful experience but also because of events occurring during the semester (ongoing pandemic, rancorous U.S. election, etc.). The Harvard undergraduate student government wrote a report, Harvard at Risk (cute allusion to A Nation at Risk), detailing the mental health impacts of the fall 2020 semester. As far as I know, this survey was a first, so it’s difficult to tell how much of a role the events of the fall played lacking data from a previous year–though we do have reports of graduate student mental health from the before times. I’m inclined to believe fall 2020 was particularly bad, based on the state of the world. So it was especially important to me to build a class environment where students felt comfortable being themselves and asking for help when needed.

I don’t know if any of my students listened to or cared about my advice during our first lesson, but I tried to be clear—their mental health is always more important than my class. They should always feel valid in asking for help, whether related to academics or mental health. My first slide of the semester was a list of mental health resources available at Harvard. The slide, of course, was insufficient on its own.

I tried my best to be easy to contact. I had a policy during the semester of replying to emails within 24 hours and following up when needed (for example, during busy office hours). Based on my course evaluations, students noticed and appreciated my responsiveness.

Another important aspect of building the classroom culture I desired was humility. I admitted when I didn’t know the answer to a student’s question, and used those moments as an opportunity to teach another crucial computer science skill—the effective use of search engines. By modeling how I respond to my own ignorance, I aimed to encourage students to ask their own questions by eliminating the sense of shame that can sometimes shroud the act of recognizing what one doesn’t know. From what I observed in breakout rooms, students helped each other very frequently, so I would argue that I succeeded in creating the positive classroom culture I desired.

Learning from other instructors

One benefit of being a student is that I can look to other teachers to see what works (and what doesn’t). In fact, one favorite training activity at CS50 is to reflect on both the most and least effective instructors one has had, and to construct best and worst practices therefrom.

Beyond that, though, I had a good number of conversations with my fellow TAs throughout the semester—how were they managing class time? How did they make breakout rooms better? How did they build a community? Having these discussions enabled us to improve together by learning from more than just our own classroom experiences; combining our knowledge proved useful in developing a better pedagogy over time.

Similarly, for the last week of the course, we were obligated to lead a discussion of technology ethics with relatively little training. (Keep in mind this is a largely technical course, so it’s not trivial to pivot from malloc to philosophy conversations without additional resources beyond the source material to be taught.) Reaching out to my own TA for a different course turned out to be very helpful in developing discussion norms and getting more comfortable with handling student disagreements. The class was actually quite fun, with students expressing regret that we had to conclude, thanks in no small part to the moderation tips my TA offered.

Conclusion

Note that one common theme is listening to others–whether to my students, my colleagues, or my own teachers. It was absolutely critical to ask my students for their thoughts each week so I could work to better meet their needs. I found it useful to talk to other teaching staff to share practices that worked for us. And I sought to create a student-focused classroom environment with many opportunities to participate, ask questions, and test new ideas. I think this made the second semester of pandemic-era online learning a little more bearable and helped my students to learn more effectively–and to feel less isolated in that experience.

Categories: teaching